Bambara Chi Wara

Bambara Chi Wara

Bringing Chi Wara to Life: The Traditional Art of Mali

The cultural heritage of traditional African art is rich and diverse. Throughout history, the people of Mali have given birth to a number of stunning and awe-inspiring artistic creations, one of which is the Chi Wara (Tji Wara). This unique art form is a celebration of nature, religion, and agriculture, and has become popular among African art collectors. Today, we will explore the world of Chi Wara, its history, and its significance in Mali’s culture.

Chi Wara is a half-human, half-animal deity that is central to the agricultural traditions of the Bambara people of Mali. This ‘working wild animal’ deity is known for tilling the soil and turning wild grasses into grain with its hooves and mother’s pointed stick. However, the people wasted the grain which led Chi Wara to return to the earth. The farmers then created art and dance to recall him and his powers over nature. This led to the creation of the Chi Wara headdress, which is the most representative form of this art

Chi Wara headdresses feature the antelope, which gave visual form to important religious beliefs about fertility and growth. These amazing headdresses were worn in dances at the beginning of the rainy season (or when a fallow field was re-seeded) to ensure a good harvest. The dancers who wore the headdresses covered their bodies with long grasses and cloth and went bent over using two canes. This is because they believed that if they stood upright, they would offend the deity. The dance consisted of jumps, sudden leaps, and turns that were reminiscent of the actions of the antelope.

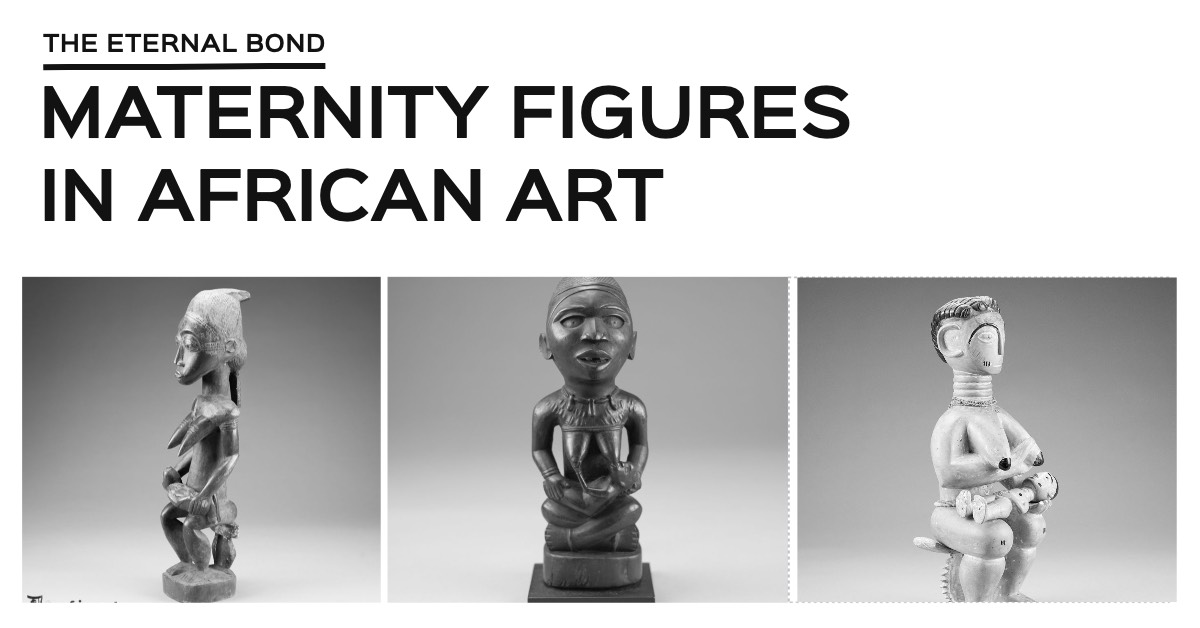

Three distinct styles of Chi Wara headdresses have been associated with different geographic areas within Mali. The first is a vertical style in which the body and legs of the male antelope are small, but the mane, nuzzle, and horns are elongated and elaborated. Its open-work mane, with a zigzag pattern, is said to represent the course of the sun across the sky during the agricultural year. The second style is a horizontal style, in which the antelope is lying down, and its body is relatively large, while the legs are short and decorative. The third style is known as the crested style that features a standing or kneeling antelope with an exaggerated mane, horns, and ears

The Bambara attributed their success to the lessons learned from a half-human, half-animal deity called chi wara, “working wild animal.” Chi wara (or tsi wara), with his hooves and his mother’s pointed stick, tilled the soil and turned wild grasses into grain. But because the people wasted the grain, chi wara returned to the earth. The farmers then created art and dance to recall him and his powers over nature.

These headdresses feature the antelope, giving visual form to important religious beliefs about fertility and growth. They were worn in dances at the beginning of the rainy season (or when a fallow field was re-seeded) to assure a good harvest.

Dancers who wore these headdresses covered their bodies with long grasses and cloth. They went bent over using two canes, believing that if they stood upright, they would offend the deity. The dancers accompanied farmers to the fields, supervised the planting, and then returned to the village where they danced. The dance consisted of jumps, sudden leaps and turns reminiscent of the actions of the antelope.

Three different styles of chi wara headdresses have been associated with distinct geographic areas within Mali. The first is a vertical style in which the body and legs of the male antelope are small, but the mane, nuzzle and horns are elongated and elaborated. Its open work mane with a zigzag pattern is said to represent the course of the sun across the sky during the agricultural year.

In contrast, the female antelope is depicted simply carrying a young on its back in the vertical style, typically found in the Segou region in eastern Mali. The second style is a horizontal representation of the antelope, accurately portraying the animal’s proportions. These headdresses are predominantly found in the northwest region of Mali, specifically the Bamako region. The third style, originating from the southwest region of Mali, specifically the Bougouni region, is highly abstract and smaller in size. This style primarily features the antelope but also includes forms of the aardvark and the pangolin (scaly anteater).

Chi Wara is a unique art form that is a celebration of nature, agriculture, and religion. It has engraved itself in Mali’s culture and has become a beloved form of art throughout the world. The Chi Wara headdresses are a powerful symbol of the connection between humans and nature that has been passed down through generations of Bambara people. As African art collectors, it is crucial that we appreciate the traditional art of this beautiful culture. The joy of having a piece of Chi Wara in your collection is the celebration of these values, and it serves as a reminder of the importance of the connection between nature and humans.

Get updates about our new items, news and information.

We will process the personal data you have supplied in accordance with our privacy policy.